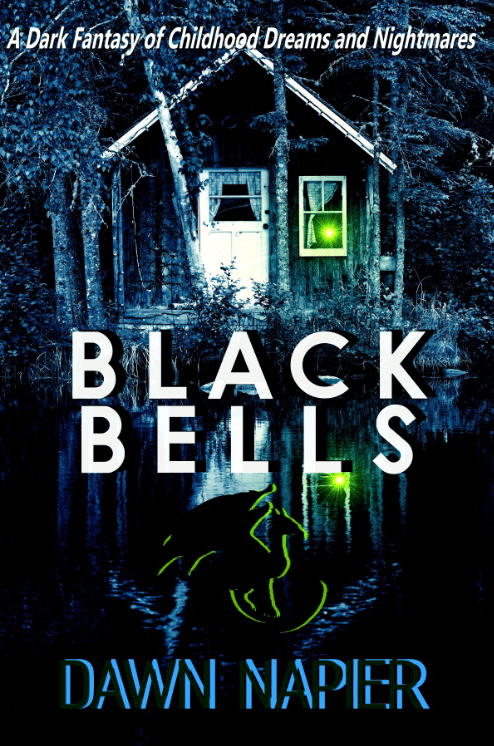

The swing creaked as Abigail Bagley swung back and forth. The rusty chains bit into her hands, but she squeezed them tighter and tighter as she swung. The air was brisk and cool, indicating the onset of evening. Soon her mother would call her in for dinner and bed. Inside the lights would be bright, and she had her Scooby-Doo night light for when Mom shut the door. But Abigail liked it outside, where it was wide open and she could see all around. It helped her not to be afraid of the well.

Mom had picked this house to rent because of the well. They didn’t have a lot of money, and Mom said that having water that couldn’t get shut off would be a great thing. Abigail understood, and in fact she liked the taste of the well water much better than the water in the drinking fountains at school. But she didn’t like the well itself. It was dark and weird down there, and the water made sloshing noises even when nobody was using it.

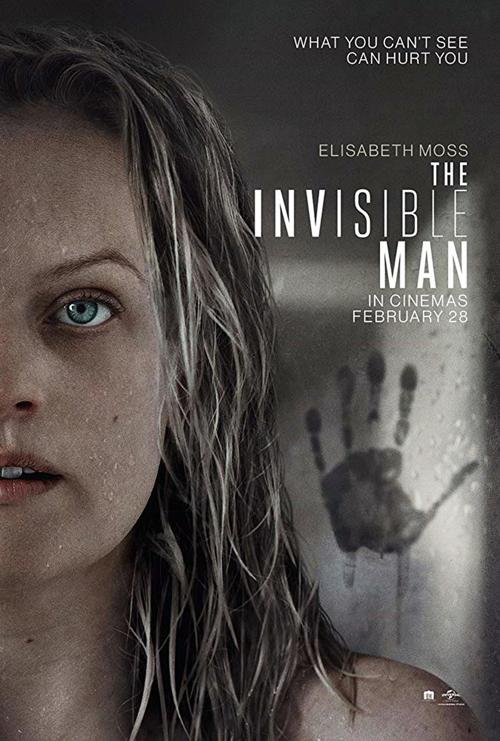

She didn’t talk to her parents about the noises she heard, the noises that sometimes sounded like voices. Daddy was back in Boston, and it was hard to talk about stuff like this on the phone. Last time she’d tried, he’d started yelling about Mom letting her watch that weird movie with the well girl. But she had only watched a minute or two before Mom caught her and shut it off. When they’d been married, Abigail had always heard Dad tell Mom, “You’re overreacting. Calm down.” But it usually seemed like Dad was the one who should calm down. The yelling had finally gotten to be too much for everyone, and now Abigail and her Mom were renting a raggedy old house on the edge of Bumblefuck, Maine. Mom didn’t know that Abigail knew the word, but Mom had said it a bunch of times, and it sounded funny to Abigail. So she said it too, but only in her head.

Talking to Mom about scary stuff was out of the question. Mom had real world stuff to be scared of, and Abigail didn’t want to make her more scared. So she ignored the well as much as she could, and she stayed out here in the open, where she could keep an eye on it. Over here on the rusty swing set, she couldn’t hear the sloshing of the water. Sometimes the sloshing sounded like voices.

The air was cooler now, and a chilly breeze ruffled her hair. It felt nice. When Abigail thought too hard about scary stuff, sometimes it felt like her head was too hot, and it hurt. The cold air washed out the scary thoughts, and Abigail felt calmer. Soon she would go inside and eat, but not yet.

There was a sloshing, slapping noise from down inside the well. Abigail put her feet down and stopped the swing. For a minute or two all was silent except for the rustle of the wind in the trees. There were no cars driving by. They lived at the end of a long, dirt road, all by themselves.

There was another splash from inside the well. Abigail swallowed. Her throat felt thick and dry.

Then she heard a little girl’s voice. “Help!”

Abigail stood up before she had time to think. The voice was panicky, and her first instinct was to rush to the well and try to see who was down there. But before she’d taken a step Abigail caught herself. She had been out here for hours, watching the well. If anyone had fallen down there, she would have seen.

“You’re not real,” she said aloud, and she sat back down on the swing.

There was silence for a while, and Abigail thought it was over. Then she heard her father’s voice.

“God damn it, Abby! Why won’t you ever listen? Get over here and look at me when I’m talking to you, young lady!”

Abigail cringed. She knew it wasn’t real, but his voice cut into her heart as though he were standing right next to him. She scrunched down into the seat and tried to curl up and make herself small. It was what she had always done when Dad started yelling, and it usually helped.

“Don’t yell at her!” That was Mom’s voice. Abigail’s breath caught in her throat. “Don’t you dare yell at her, it is not her fault!”

Then she heard it: that horrible sound that had ended her parents’ marriage and torn their family in half. That flat, lifeless slap of Dad’s hand across Mom’s face.

Abigail jumped to her feet. “Don’t you dare!” she shrieked. “Don’t you touch her, you big mean bully!” Her heart pounded in her chest, and she felt like she might explode from the rage and fear that flooded her body.

Silence again. Abigail panted hard and tried to calm herself. She was halfway between the swing set and the well, though she did not remember moving at all.

Then she heard a low, horrible chuckle. And the sloshing sound from the well came again. Louder. There was something big and heavy in there.

“You’re a smart one,” whispered the voice from the well. It didn’t sound like Dad or Mom. It sounded low and chuckly, like some awful being telling a joke. “Took me a few tries to find your button. But here we are at last, and here I come.”

All the strength went out of Abigail’s legs, and she fell on the ground. She put her hands out and tried to scoot backwards, but the sloshing sound was getting louder. Now there was a clawing, dragging sound coming from the well. Something was climbing the brick walls, pulling itself out.

“Oh please no,” she whispered.

“Oh please yes,” the chuckling voice responded. The well cover shifted and opened a crack. A small grey hand emerged. Its fingernails were black and filthy. Then the voice changed back to the little girl from before. “It’s so cold down here, Abby. Don’t leave me alone. You’ll like it down here.”

“Oh no please,” Abigail said again. She scooted backwards on her butt, but she still couldn’t find her feet. The thing was coming out of the well, and she didn’t know how to stop it. Soon it would come get her, then it would come get Mommy. Mommy had watched the movie too. Seven days ago.

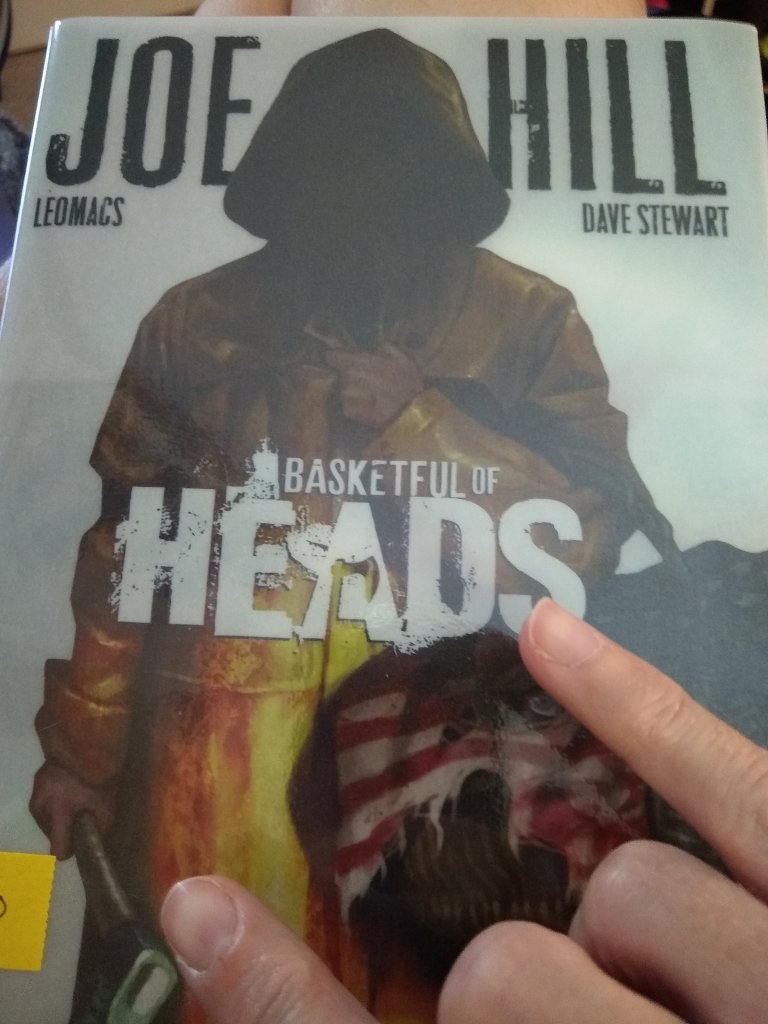

“You’ll like it down here. There are lots of kids to play with. Kids just like you, who won’t laugh at your old clothes or your Mom who doesn’t have a man. We have so much fun down here. We play, and we float. We all float down here.”

The hand was followed by an arm, then another arm. Then the horrible head, full of stringy black hair that dripped with well water. There were other things in the well girl’s hair. Things that squirmed.

“We… all… FLOAT!”

Abigail screamed. The dead girl lifted her head and grinned, and her mouth was full of thin, jagged teeth. Her face was white and smeared with what looked like white makeup and bright red blood. “We all float,” the dead girl whispered around her mouthful of teeth. “You’ll float too.”

The thing from the well crawled slowly, slowly towards her, and Abigail scooted backwards. She still couldn’t find her feet.

It was getting closer.

This felt like the bad dreams she sometimes had, when she tried to run but her arms and legs were weak and stiff and she couldn’t move. The thing crawled closer.

Then Abigail took a deep breath and screamed, “I didn’t watch the cursed video!”

The thing from the well hesitated. Abigail went on, “I only saw the part at the end where the dad died. My mom told me the rest. I never saw the part that kills you!”

The dead thing from the well went very still. It was almost as though someone had hit the pause button. Abigail scrambled to her feet and ran into the house, panting and sobbing.

Inside, Mom was talking on her phone. She set it down as soon as she saw Abigail come in. “Are you okay?” she asked. “What happened?”

Abigail threw herself into her mother’s arms. “I don’t like the well, Mom,” she whispered. Mom’s hair was warm and smelled nice. Abigail closed her eyes and breathed deeply. She could finally breathe.

“Sweetie, we’re not going to stay here anymore,” Mom said. “I just got done talking to the landlord. The house is way more broken than he said it was—that well is about the only thing that isn’t falling apart—and another kid disappeared last night. I’m done here. We’re done. Your dad says there’s a nice place not far from him and Kristen, and we’re going out there this weekend to check it out.”

Abigail gave a long, shuddering sigh. She felt like she might fall asleep standing up. “Good,” she murmured. “I hate it here.”

She disengaged from her mother and went to the back door to look out. A small, grey hand disappeared into the well, and the cover moved back into place. “You can’t get me,” she whispered.

Then she went into the bathroom to wash her hands for dinner.